Food. It surrounds us.

Often in mind, cooked into material by consciousness or ordered to home by food delivery apps. Used in daily idioms and tricolons — “we eat to live, not live to eat” and “sugar, spice and everything nice” — food has, since the beginning of time, written the syntax of our daily lives.

Be it Adam and Eve, whose first quarrel arose from an apple, or the lucrative imports of Indian black pepper that China coveted, food has prevailed in wars, peace, and everything in between.

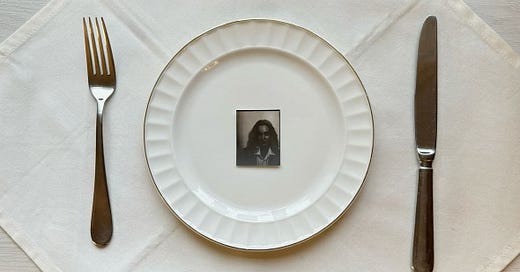

But what happens when food — the ritualistic apogee of being — is aberrated to challenge it?

Hunger, the buyer of food, has historically been used in significant political and religious movements — to catalyse improvements and to inhibit amendments.

The psychology of hunger begins with the basic and dangerously innocuous foundation of necessity. In Maslow’s hierarchy, we see that food is at the bottom of the pyramid, symbolizing its indispensibility. Its truth — naked, simple, and urgent — is tethered to its existence. Without food, one cannot survive.

Hence, the display of forfeiting food — the building block of life — in the fight for a “greater good” demands people’s attention.

Gandhi is a popular name that comes to mind. He often used hunger strikes to evoke emotions and rally people for the cause he believed in. He did it in 1917 for the farmers in Champaran, in 1932 in protest against the separate electoral system, and again in 1943 against the colonial policies during the Quit India movement.

But how did it command such kinetic national attention? There are two main reasons:

One, the body is both the pinnacle and vehicle of mortality, as aforementioned. The body itself — the most vulnerable part of a human — is used to explore the world. Thus, to invite a self-imposed degradation upon it is the utmost sacrifice for the greater good.

Secondly, hunger strikes throw the oppressor into a psychological paradox. From the protestor’s end, they have embarked on the path of self-sacrifice. However, on the oppressor’s side, they face political pressure — in case they are immune to the moral one — to act, lest the protestor dies a “noble” death.

The will to survive versus the will to exist entraps people in a conundrum, whose answer is processed as visceral support.

Previously, hunger was seen as a form of purity of body, transcendence of the worldly realm, and clarity of mind. Mystics, saints, and venerators alike all took part in this culture, looking to satisfy specific instrumentalities of their being.

Jainism, Islam, Hinduism, and Christianity are all religions that have had a long history of fasting — to reduce karmic debt, obtain spiritual growth, or seek blessings from deities.

This gospel of hunger separately preached a vignette of feministic corporeal control.

In a world that feeds on physical vulnerabilities, women have been the Sunday hunt for years in the lunch of expectations around beauty, sex, and submission.

In Sylvia Plath’s The Thin People, she says:

“They are always with us, the thin people... Meagre of dimension as the gray people / On a movie-screen”

She portrays the “thin people” as omnipresent, inescapable shadows of self-erasure — constant reminders of the societal expectation to reach the two-dimensional and starving “perfection.” A role projected onto them like a silent film they cannot stop watching.

Hunger was utilised as a paperweight on the featherlight demands of feminine freedom.

Advertisements, conversations, branding, attitudes, societal structuring — they coarsely homogenised women into claustrophobic cubes. Hunger became a performance of purity. Who was more virgin, more fragile?

The only way to beat the system was to use hunger against itself. So, hunger was employed as a tool of restraint — a shield of control against a world that was always exercising corporeal control outside its jurisdiction.

The question of restraint, thinness, and fragility reaching peak validation and praise grew stronger with doubt when no one could see the repercussions- till it would finally turn to sickness.

The issue of modern hunger is far different from its ancestral forms.

In an era of connectivity fostered by efficiency, where the politics of hunger are less profound, what deficit do we still face?

The displacement of modern hunger has been created by the ubiquity of technology. Since our capacity for physiological hunger is almost always satisfied, a parallel hedonic hunger for everything else is born.

Scrolling, shopping, self-help feeds the newer generation of tech users.

It is fuelled further by the presenting of curated, idealised forms of life, driving consumption of both goods and attention. Each swipe raises the ceiling of satiation — and the eventual end of it is, well, not eventual at all.

Since we don’t starve our bodies, we binge on everything else. The endless appetite for genuine joy takes one away from the real capacity for contentment.

If there’s one thing that’s clear from the history of hunger, it’s that it will always reincarnate itself in different forms. Why? Because in a world where a section of the population wants to be at the top, there will always be a subsequent section at the bottom.

Hunger wields the power to make, break, and maintain standards — its form obscure, but perennial.

The best way to shield oneself against such expressions of force is to reach the capacity for content — i.e., identifying the consciousness around consumption.

Food, validation, ideals, and experiences have culturally led to mindless consumerism. To remedy that, one must reclaim agency.

This retrieval is an act of self-redemption identified through rebellion — but one must be willing, within themselves, to take up the challenge.

A great article emphasizing on the nature of hunger not just in its literal sense of perception but as a modern tool of influence with regards to irrational consumerism!